Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship.

Romans 12:1

Last updated: June 2, 2025

Theokinesis (θεόκινησις) is a Christ-centered movement, study, and performance art system that invites participants of all backgrounds and abilities to engage in body-based art, dance, and theatre inspired by scripture. In Theokinesis, the body becomes a vessel guided by God, as participants surrender to a body of prayer. The practice fosters creative flow, encouraging spontaneous expression and presentation.

THEO – God

He alone is my rock and my salvation, My stronghold; I shall not be greatly shaken.

Psalm 62:2

Christ is The Rock that doesn’t move. He is Unconditional Love, a palm sustaining us. He is The Groom and The Ground, both our salvation and the dance floor.

Any mention of God in Theokinesis points to God as Father, Son, or Holy Spirit. Furthermore, any mention (in class) of Source, Divine, The Most High, Wellspring, etc. also simply means God.

KINESIS – Movement

The Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

Genesis 1:1:2

Kinesis is motion. While internal motionless motivation for prayer may be the starting point, it must go further. Imagine loving someone but never expressing it. Hence our prayer is a dance.

When motion is taken further, it is the Holy Spirit. This Holy Spirit cannot be earned through actions, but is rather received through surrender to God and faith (trust) alone. Even then, it is still at God’s discretion.

At the beginning of Genesis, this Holy Spirit moved gracefully upon the waters, symbolizing the union of the material and spiritual.

A later illustration of this union became the sanctification of The Holy Virgin Mary, who represents both Matter and Motherhood, thereby exemplifying the divine blessing bestowed upon Creation by God. It is through the Holy Spirit entering Mary that this sanctification was realized (Luke 1:35).

* * *

In Theokinesis, the goal is to establish a personal relationship with God, responding through the body, and transforming into a mystical servant. The body and immediate space become the church.

The practice grew from a desire to create a new chapter in the world of butoh dance theatre where a powerful Christ-centered sacred dance could occur.

Butoh founder Kazuo Ohno’s Christian Faith

Butoh while certainly not associated with Christianity has had its intersections with it. First off, butoh’s co-founder, Kazuo Ohno, had always identified as a Christian. His first performance outside of Japan in 1980 even took place in Nancy, France at the Church of St. Fiacre where he performed Invitation of Jesus. Then two weeks later, he would perform the same piece in Paris at Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas Church.1

See a short video recitation of Kazuo Ohno’s poem Invitation of Jesus here.

Yoshito, Kazuo Ohno’s son, explained how, for instance, Kazuo practiced his Christianity in butoh where expressions such as “God is great” or “Thank you” were not verbalized but instead expressed in his butoh.2

Yoshito once asked Kazuo to show him how being a Christian was related to being a butoh artist. Kazuo responded that he would embark on a pilgrimage to Bethlehem, considering it a return to his spiritual birthplace, “as if Christ is walking” (Nakamura interview). The pilgrimage culminated in the The Dead Sea in 1985, where both Kazuo and Yoshito took part. Although Tatsumi Hijikata choreographed Yoshito’s dance in this performance, it was Kazuo whom Hijikata commented on after the show, saying, “Finally, a spiritual butoh dancer came to us.”3.

Kazuo Ohno would go on to perform The Dead Sea a total of 37 times throughout the world.

See a short video recitation of Kazuo Ohno’s poem Invitation of Jesus here.

Butoh founder Tatsumi Hijikata’s Final Moments

Tatsumi Hijikata, the other co-founder of butoh, infused the dance form with its darker undertones. He frequently criticized Kazuo for his belief in God. However, in a surprising revelation at Hijikata’s deathbed, to the astonishment of Yoshito, he confessed that his ultimate fear was God, and his parting words were: “In my last moments, God’s light . . .”4

See a short video about this here.

* * *

Theokinesis takes off where the Ohnos were in their personal life and where Hijikata left off—with God.

Theokinesis draws inspiration from the entirety of Christian history, encompassing saints, Christian mystics, and the early desert fathers. It establishes a foundation in both Orthodox and Catholic canons without seeking to deviate from them.

Any divergence from scripture identified either by guide or witness should be acknowledged and rectified. Theokinesis is meant to be tested biblically so as to keep a sound integrity.

Theokinesis is a growing pedagogy and so is consistently tinkering with itself.

Theokinesis article | Mar 2025 | Issue 9 | ICDF (International Christian Dance Fellowship)

Theokinesis article | Mar 2024 | Issue 5 | ICDF (International Christian Dance Fellowship)

A Spring 2025 seminar in Tbilisi, Georgia about Theokinesis.

Movement as Prayer

My butoh is a prayer.

Yoshito Ohno5

Prayer is any address toward God. When dance or movement is prayer, this means that our movement is focused on God in some shape or fashion and becomes a prayformance.

Why Butoh?

So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.

2 Corinthians 4:18

Of my 14 years of exposure to various genres of dance or movement—Modern, Ballet, Jazz, Contact, etc.—the genre that has by far captured the most depth, physically, mentally and beyond, has been butoh.

Intersections of Butoh & Christianity

Because butoh possesses an inherently otherworldly or spirit-filled quality, it has the ability to align with the Christian practice that is also otherworldly and spirit-filled. This is how it was able to align with the co-creator of butoh, Kazuo Ohno, a devoted Christian.

Kazuo Ohno, however, is not the only person to have practiced butoh within a Christian lens, but since August 2010, the Manhattan-based butoh artist Marilyn Green has led a group of butoh dancers and chorus in Christian-based butoh at a church nearby the former Twin Towers.6

Christian Mysticism & Butoh

To embody the tenants of Christianity deeply in the body lends itself to a form of Christian mysticism. What exactly do I mean by mysticism here? It’s simply a raw form of Christianity, one that foremost involves a relationship with God instead of relying too heavily on an institution. In a relationship with God, naturally, visions and insights are illuminated. That is the “mysticism” side of Christianity.

So though butoh in general is a practice of spirits (and those who are secular may call them qualia or worlds), it is important to discern that not everything that is of sprit is truly beneficial. “Spiritual” does not automatically mean benign. Butoh, throughout its history, has been more of a neutral artistic tool, not inherently related to any faith, and susceptible to misuse like any other life activity.

Commonly, butoh has been viewed as a dance of transformation where shadows or the subconscious are the material for dance. But just as “spiritual” is a neutral term, so is “transformation.” What exactly do we mean by transformation? Sometimes a transformation may simply be something allowed to fester and ferment, and not all things that ferment are wholesome. Sometimes butoh shadow work is “butoh bypassing.” Sometimes destructive behavior can be enabled under the excuse of embodied art or self-help.

Nietzsche once said the famous quote, “Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster.” Yet, I feel more accurately, it should also have included “or befriending monsters.” While fighting or ignoring one’s shadows can certainly turn one into the thing one is trying to fight or ignore, the case can also ring true for “befriending” shadows.

In Theokinesis, we sometimes simply have to cut things out or put them on the cross. To quote Matthew 5:30, “And if your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to go into hell.”

Theokinesis uses butoh like a contemporary church would use a guitar. On its own, a guitar is neutral. Consider what butoh would look like after it were plunged into baptismal waters.

Butoh, Christianity & Paradox

Butoh scholars Helena Katinkoski and Jochelle Elise Pereña proposed that paradox was one thing separating butoh from any other art form. Katinkoski claimed butoh was “a liminal art that arrives to non-dual performing by embodiment of a paradox,”7 and similarly, Pereña claimed “[Butoh] is a liminal art, meaning that it is part of the threshold or limen between worlds, and it is also part of both worlds – a paradox.”8

“Bipolar oppositionalism” coined by Arata Isozaki is what Katinkoski felt Hijikata based his butoh on such as death being life and ugly being beautiful.9

What are some other common paradoxes associated with butoh in general?

- Debilitated yet lively

- Obscure yet expressive

- Infantile yet genius

Curiously, scripture is teeming with paradox or what I call Christian koans, many of which intersect eloquently with butoh, especially with the common motif of vulnerability.

- Weak yet strong: We gain strength by being weak. (2 Corinthians 12:9-10)

- Foolish yet wise: We are fools for Christ. (1 Corinthians 4:10)

- Dead yet resurrected: I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. (Galatians 2:20)

- Enslaved yet free: But now that you have been set free from sin and have become slaves of God, the benefit you reap leads to holiness, and the result is eternal life. (Romans 6:22)

- Infantile yet saved: Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 18:3)

There are too many to reference that could make for great butoh embodiment. So paradox itself is a another otherworldly intersection between butoh and Christianity.

Navigating Labels

Some would suggest eliminating the butoh label entirely and framing Theokinesis as a creative free movement practice or physical theatre in the same way Min Tanaka distanced himself from the label and wanted his practice to simply be Body Weather. This is a matter of preference, considering the desire to acknowledge origins and the impact a practice has had on its current form.

Butoh’s Liberating Essence

Regardless, butoh stands out as an exceptionally free movement practice, arguably the most free, alongside perhaps Janet Adler’s Authentic Movement which I’ve had limited exposure to. On top of that, butoh’s use of butoh-fu (butoh notation) is an incredibly rich way in which to form a multi-faceted completely embodied dance theatre that breaks old movement patterns and inefficient habits.

Ultimately, the crucial aspect in Theokinesis is the communion of one’s body and movement with the Holy Spirit and the resulting theatre ministry that follows.

Butoh can help us go beyond a lukewarm Christianity, where we can take on an active, embodied role in our relationship with God.

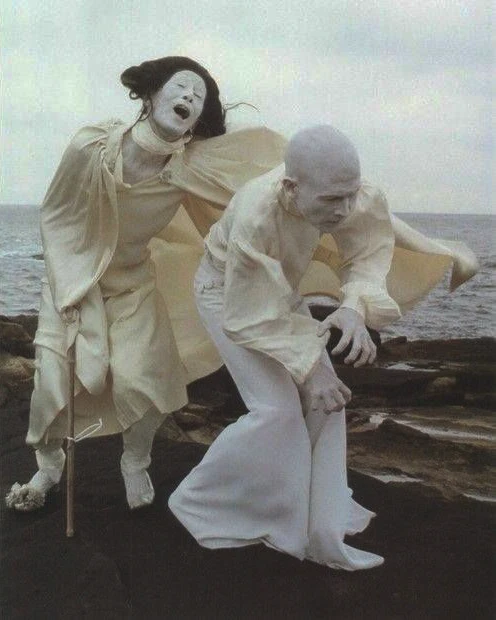

Theokinesis-based performance performed in Chennai, India.

See the butoh-fu (choreography) here.

A Guide’s Responsibility

Not many of you should become teachers, my fellow believers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly.

James 3:1

Theokinesis adheres to biblical canon, and so any deviation ought to be addressed and rectified. As the quote above shows, the stakes are high for the dance minister.

I end with a quote from the dance minister Marlita Hill:

We till the heart as we lead the people in praise and worship, as we lead them in gratitude toward God, and as we lead them in remembrance of who God is to them and for them, and what He has done in them and for them.10

- Ohno, Kazuo. An Invitation to Jesus. Dance Archive Network. https://dance-archive.net/en/archive/works/wk6.html ↩︎

- Ohno, Yoshito (1999) Ohno Kazuo: Tamashii no kate (Ohno Kazuo: Bread/Food for the Soul), Tokyo: Firumua ̄tosha. Page 23. ↩︎

- Fraleigh, Sondra (2006) Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo. Page 67. ↩︎

- Ohno, Kazuo and Ohno, Yoshito (2004) Kazuo Ohno’s World from Within and Without, translated by John Barrett, Wesleyan, CT: Wesleyan University Press. Page 137. ↩︎

- Mizohata, Mina. About the Kazuo Ohno / Yoshito Ohno Digital Archive. https://dance-archive.net/en/features/features_50.html. 2024. ↩︎

- Green, Marilyn. Choreography. Marilyn Green Art. https://marilyngreenart.com/choreography/ ↩︎

- Katinkoski, Helena. “Non-performing – Liminality and Embodiment in Butō Dance”. BA Thesis. The University of Stockholm.2017. Page 44. ↩︎

- Pereña, Jochelle Elise. Chasing shadows: Exploring Butoh and the Liminal. M.F.A. Mills College, 2011. Page 9. ↩︎

- Ibid. Page 17. ↩︎

- Hill, Marlita. Dancers! Assume the Position: The What, the Why, and the Impact of the Dancer’s Ministry. 2014. Page 62. ↩︎